Public monuments and infrastructure often gain a lovely patina from people touching them over the course of decades and centuries. Digital public infrastructure gets warped hardware, malfunctioning screens, and internal fogging in months.

I want to write a little bit about LinkNYC. For people who aren’t from New York, LinkNYC is a collection of megalithic digital screens that look like the love child of the tablet from 2001 and a phone booth. Over the last few years, they’ve also mostly replaced phone booths across the city.

‘Mostly’ because they perform similar functions: a space for advertising and the ability to make calls. ‘Mostly’ because you can still occasionally find a phone booth next to them, still standing with years-old advertisements and a missing handset.

These giant tablets also provide free WiFi hotspots across the city. I see them pop up anytime I need to connect to WiFi and I’m below the fifth floor of a building on a non residential street. I instinctively don’t trust them. I remember when the headlines were all about London’s “smart” trash cans snooping peoples mac addresses, leaking data, and being malicious middlemen. So no thank you. Free-as-in-mousetrap.

But it’s an audacious plan and rolled out mostly well. From the perspective of a potential advertiser, if you replace print billboards with digital ones, you end up cutting down the cost of production, increase the number of ads and a/b variants you can display, make it easier to geo/chrono-target, and make it easier to deploy and optimize campaigns. It’s like Facebook ads IRL. (I work in marketing and advertising, so I think a lot about these things).

The phone and WiFi stuff feels almost incidental. It’s a way for the city to get public buy-in, because I don’t think that anyone really thought that spending public funds on this was a great idea. Except for maybe old men in government.

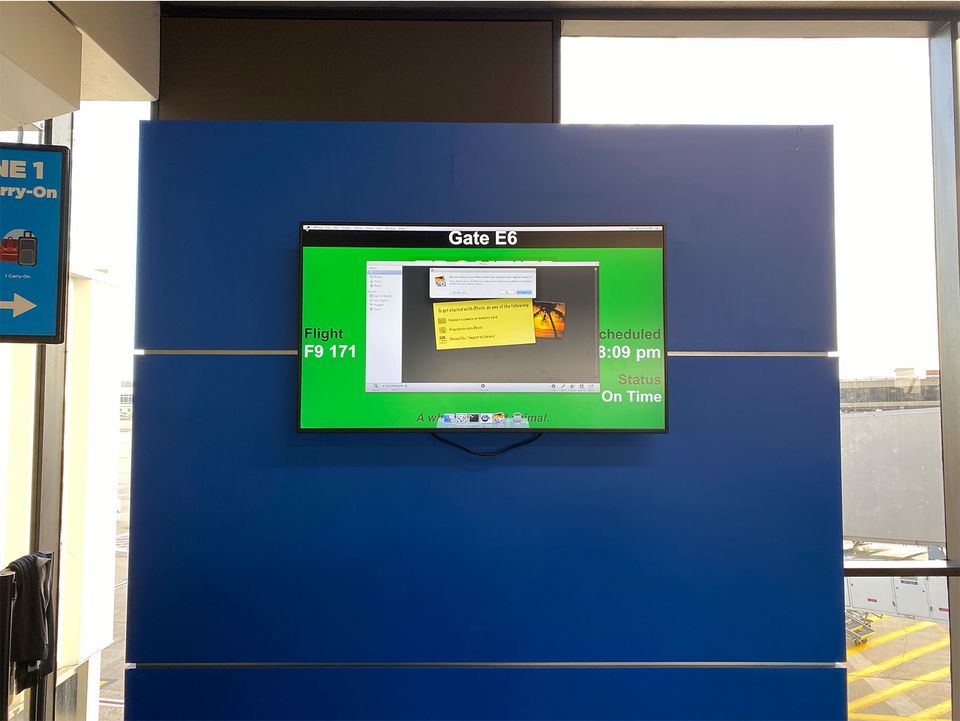

Of course, with a huge footprint things are bound to go wrong eventually. The most obvious starts with the hardware itself.

In modern DevOps, there are a lot of best practices that you can follow to ensure minimize errors and downtime as you run a distributed digital system. There’s a whole field called Software Reliability Engineering around this. You’ve got failover states, cascading checks, and a lot of things to mitigate the failure of one node and distribute the load across others. Virtualization and rules-based setups further let you spin up or down to handle loss as needed.

But when that system is physical, you end up with something different: all the drawbacks of digital systems (complexity, troubleshooting, lots of possible error states) and none of the benefits of virtualization (as in, you actually need to fix it in person; geography isn’t abstracted away; if something fails, you might not be able to run remote diagnostics.) (I dabble in digital ops, so I think about this stuff too).

Food for thought: what are the best practices for running non-virtualized distributed digital systems?

The most obvious thing that could go wrong is with the hardware.

And it does.

Not too often, but it does so in noticeable ways. Warped screens. Malfunctioning screens. Internal fogging. There hasn’t been much in the way of scratched screens, but people do place place stickers on them. Sometimes the screens are just inexplicably off. Are they broken? Who knows?

The next hard thing about designing technology for public spaces is that you have to deal with the public and the space.

The public will criticize any perceived issues and will wear through most things purely by touching it. Just look at any bronze statue polished gold, or marble staircase worn away by footsteps. Now imagine a button (or screen!) designed to withstand those levels of interaction.

Then there’s the space. You have to design for a range of elements. If you weatherproof too hard, you lock yourself out of internal maintenance. If you don’t weatherproof enough, you’re leaving yourself open to all kinds of mechanical and electrical failures over time.

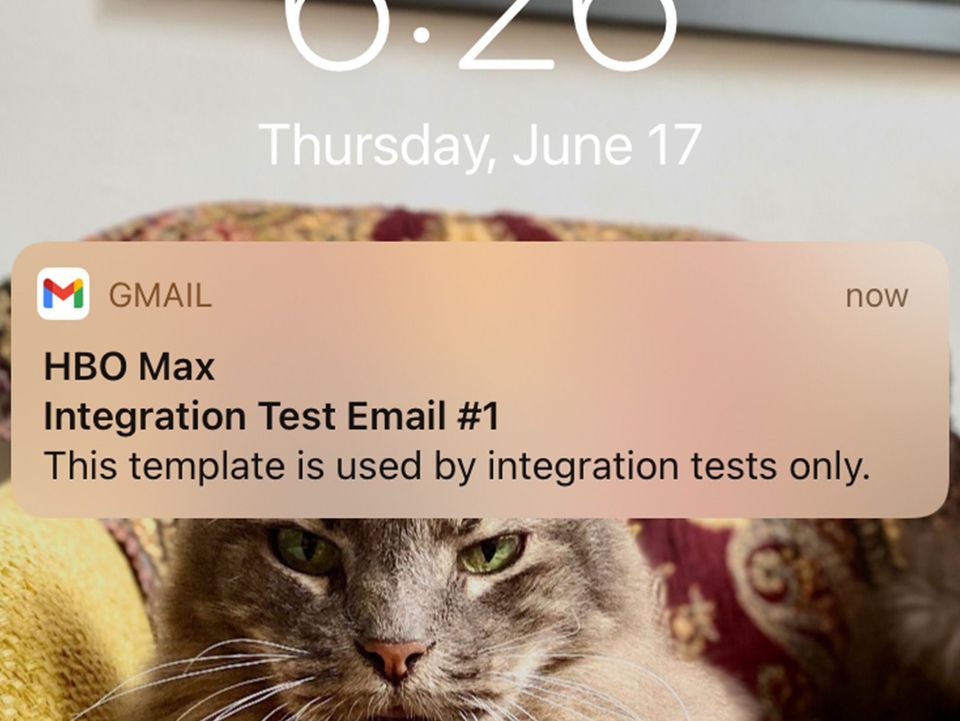

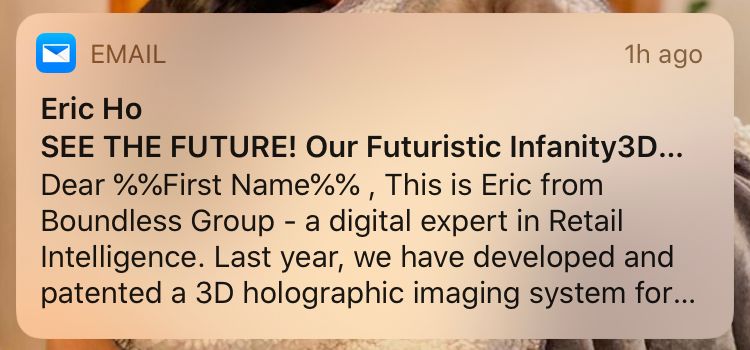

You have the software failures. A bad file uploaded and distributed that somehow ends up crashing the display. A bad update that causes issues on boot. Malicious activity to force the local LinkNYC down. Something - god knows what - going wrong because… well, because computers. I love how stereotypical some of these are: the blue screen of death. Lines of text streaming sideways down the screen like they’re in an audition for The Matrix. These happen as often as hardware bugs.

All things considered, I don’t see too many issues. Maybe 1% or 0.5% of the screens I encounter have anything wrong with them. I’d reckon – busy doing some Google-interview-level-math – that at 100 major streets and 11 major avenues, with 2-4 screens per intersection as a baseline, then you probably have 3,300 screens rolled out across midtown and downtown Manhattan (below 59th street). At a failure rate of 0.5% per day, that’s still 16 or 17 screens that need fixing daily.

And then, how do you recognize hardware failures? If a screen is malfunctioning or has dead pixels, it’s not really something that you diagnose with a ping-for-a-response. I see screens go unfixed for days because of this. (Coincidentally, I’ve never once seen anyone actually repairing these. They just seem to sprout up like mushrooms, get turned on, break, and work again with minimal human intervention.)

But more to the point – when you’re running a non-virtualized system at scale and you have a 0.5% failure rate on things that you can’t easily failover or needs physical intervention for repairs… what do you do?

So that’s kind of it: I suppose the big question driving this blog is the discovery of that knowledge and expertise as we slowly but surely digitize more of our public spaces. Most of the exploration is on the easily-visible public issues, but there’s a lot to say about the 99%-invisible-type stuff too. Hope it’s as interesting to you as it is to me.