The "cloud" is really just a bunch of computers in someone else's closet, connected by literal pipes and wires.

Well now.

Is it fair to call the COVID-19-initiated crisis the biggest error state of our world economy and healthcare system? Too soon?

Ok. I’ll write about other things, such as the internet. With many more people suddenly working from home, or simply being home without an opportunity to leave, the internet-as-infrastructure grew severely strained at the end of March.

In a couple of memorable instances, it broke.

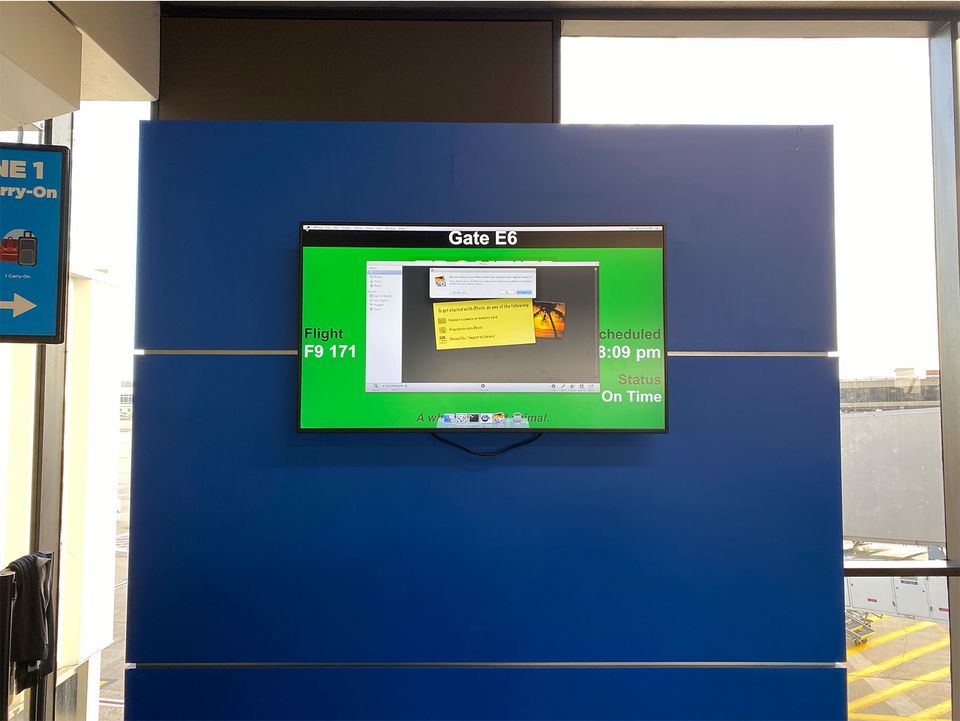

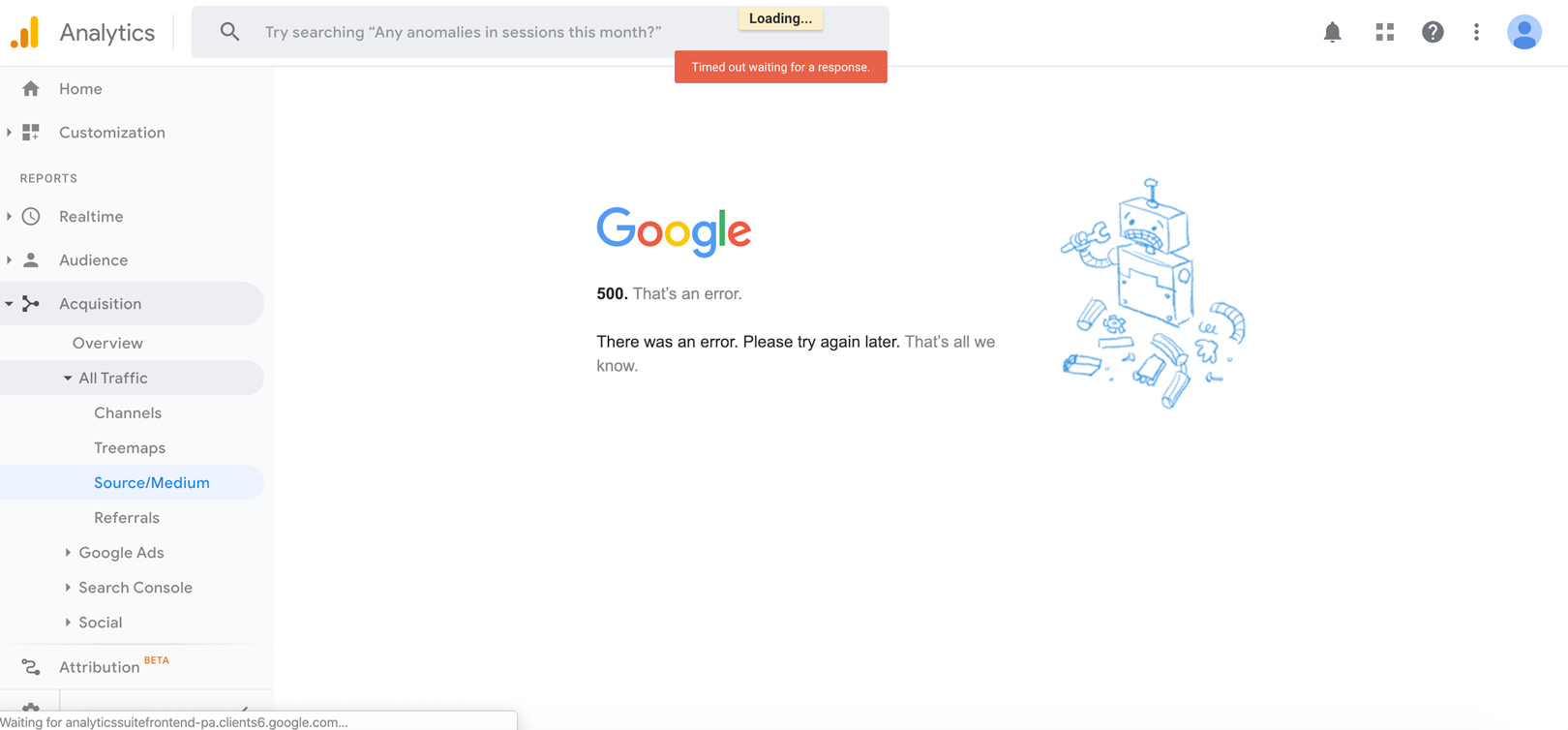

The title image is me trying to access Google Analytics as part of my day job. Earlier, even their error messages were giving me error message:

You know the error message is having an error message when it doesn’t align with Material Design standards.

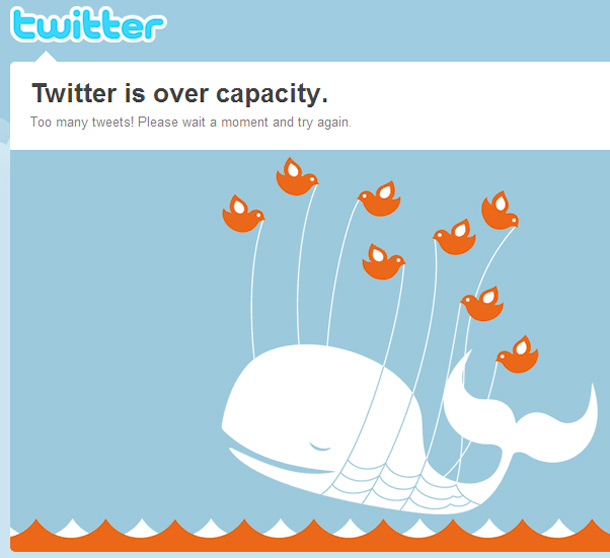

One can write an interesting history of the internet through the lens of error messages. For example, Twitter’s infamous fail-whale was the perfect metaphor for rapidly growing internet companies in the aughts, when their infrastructure couldn’t keep up with how quickly people were joining and using the platform:

Or going a little deeper, do you know what all of the HTTP status codes stand for?

1xx informational response – the request was received, continuing process

2xx successful – the request was successfully received, understood, and accepted

3xx redirection – further action needs to be taken in order to complete the request

4xx client error – the request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled

5xx server error – the server failed to fulfil an apparently valid requestThe 200, 301, 404, and 500 status codes are the ones most people are familiar with (the 200 means your request was fulfilled - if you load in a site, you’re logging a 200 status).

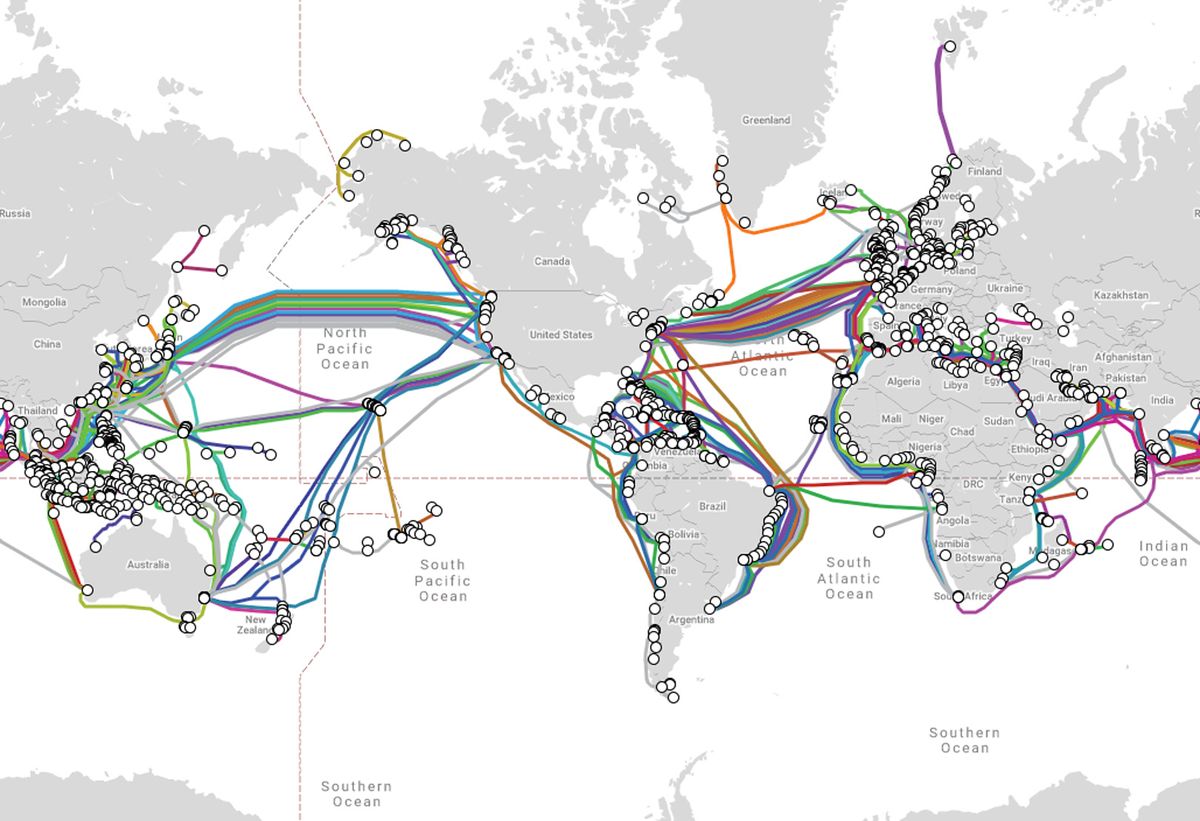

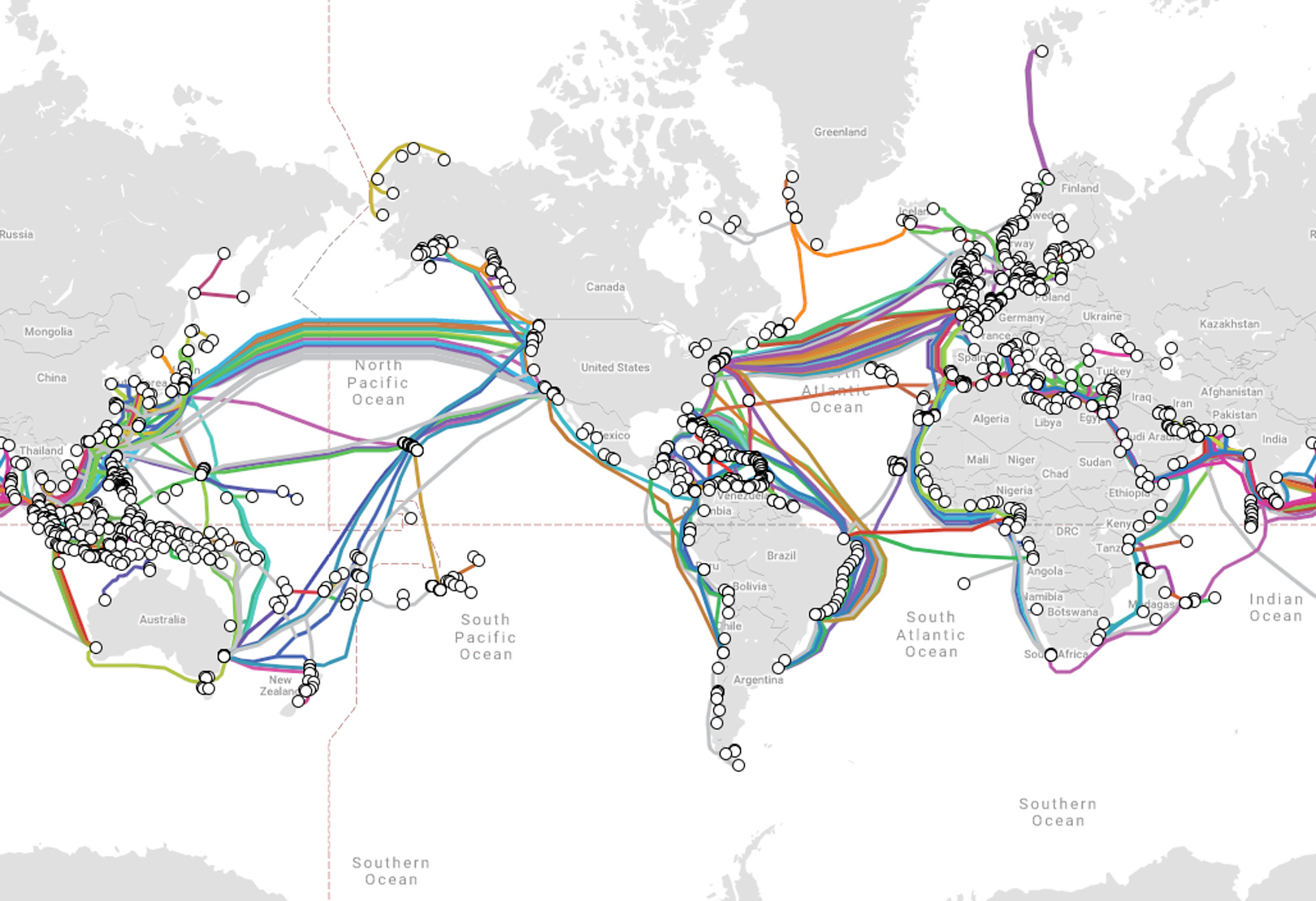

Let’s go deeper still, into the wires themselves. Do you remember the memorable instance when a 75 year old lady in the Republic of Georgia was digging for copper and accidentally cut the fiber optic cables that connected neighboring Armenia from the internet?

Yes, the internet is really just a bunch of wires connecting data centers:

Sometimes it is easy to remember this.

Michael Lewis wrote a fascinating exploration of internet wires and latency while ostensibly talking about high-frequency trading in “Flash Boys”. When your arbitrage depends on acting on information received seconds or milliseconds faster than others, the length and bandwidth of those internet wires matters a great deal. (The climax of the expose was with a stock exchange that bucked the trend by making everyone equally slow to straighten the odds).

Or take bitcoin mining, when a lot of people went out and purchased industrial-sized quantities of processors, hooked them together and connected them to the internet. It wasn’t that different from the late 90s and early naughts when running your website from a home-computer-as-a-server was still possible, and when most companies still had their own server farms. The biggest difference was that - in Iceland, at least - bitcoin mining ended up costing more in energy than powering all the homes in the country. As an interesting bit of trivia, bitcoin mining today seems to be done efficiently only by literal power plants.

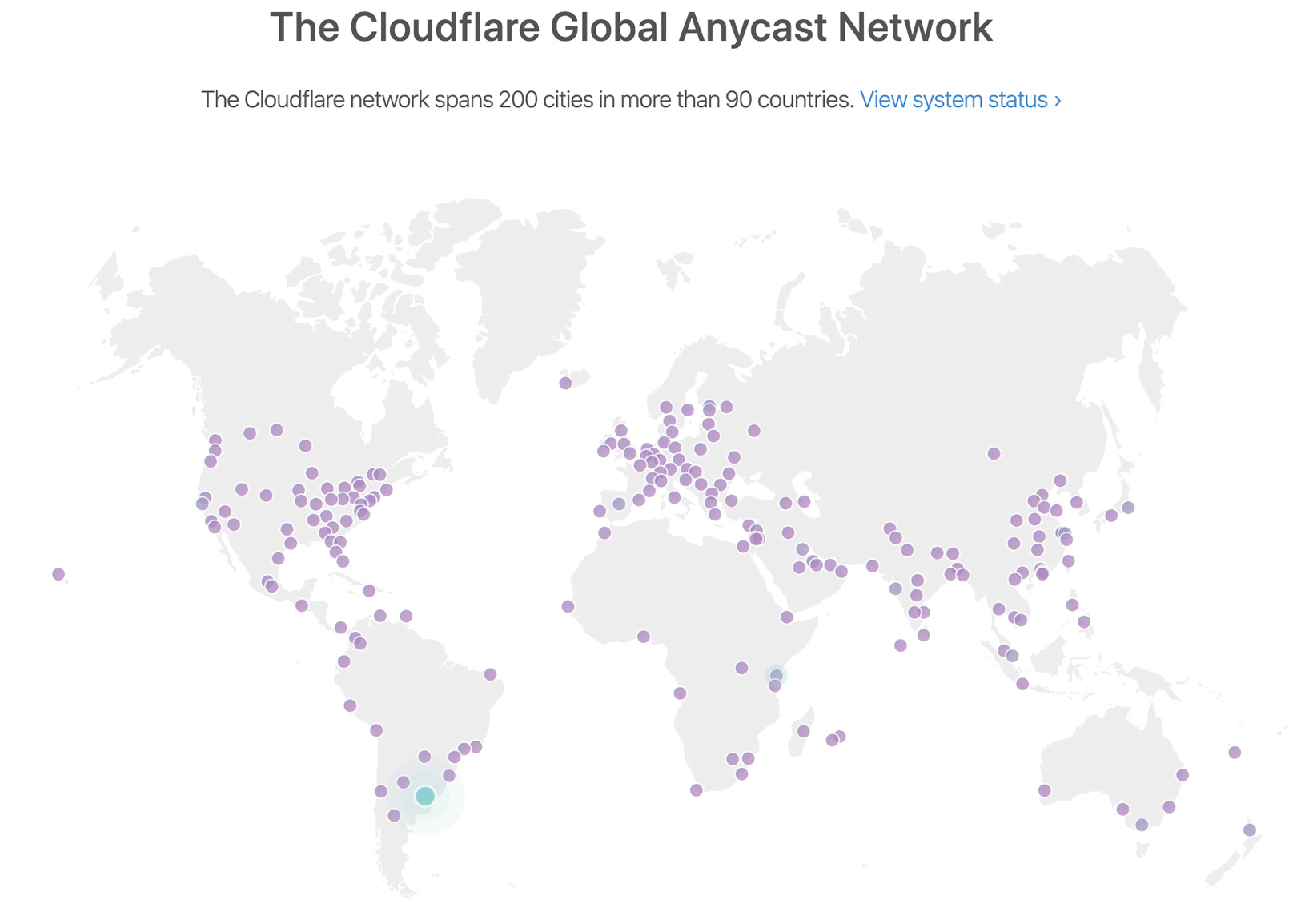

If you work in the web technology space, you probably rely on CDNs (Content Delivery Networks). Using a CDN means distributing your content to multiple locations so that it can be served to you from the closest one. If you’re in the middle of Turkey, you’ll get your content from the Istanbul CDN location; if you’re in New York, from the New York one. It keeps things working fast and creates safety-through-redundancy.

Sometimes, it is harder to remember.

If you’ve grown up after the 90s, or if you’re not too tech savvy, it can be easy to forget about pipes and wires. It just works, right? The internet is in the air. It’s present.

Even if you’re tech savvy, virtualization is a major buzzword for forgetting the physicality of the internet. First you outsource your servers to someone else. Then you make those operating systems run virtually, in containers. The promise is of near-infinite scalability on demand. The reality is that scalability only extends as far as your provider has capacity for it scale to. Like Uber’s “Surge” pricing (it goes up when everyone wants a ride), Amazon Web Services (AWS) manages this as a marketplace that automatically scales prices in response to demand.

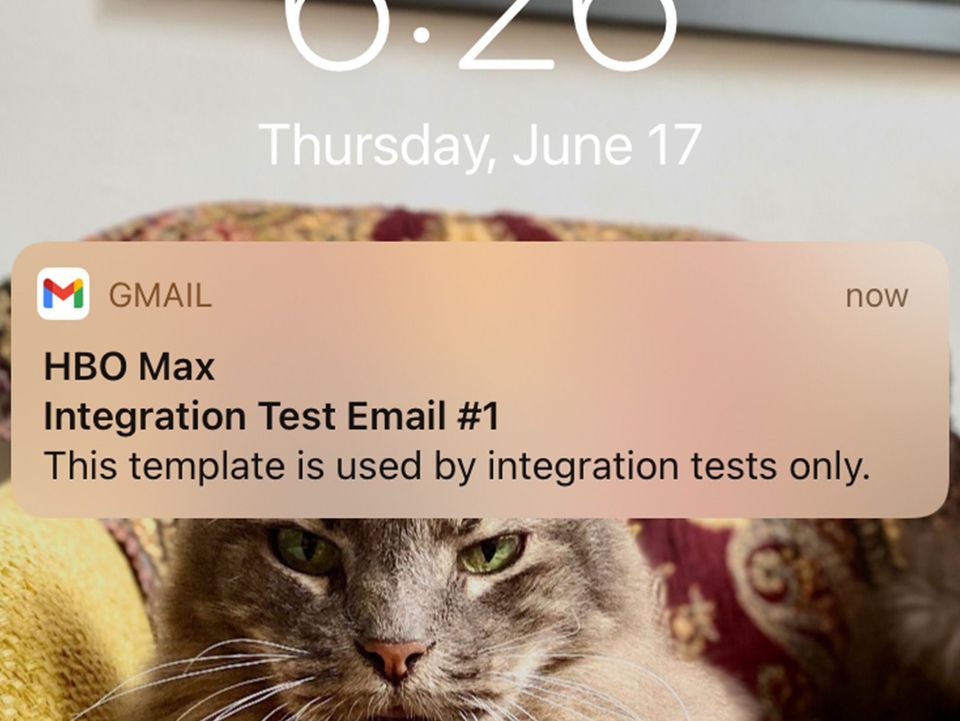

Google (GCP) and Microsoft (Azure) do this too, but they’re 2nd and 3rd and are still trying to make it work. They have less users than AWS, and consequentially less capacity. So when Azure’s demand went up more than 775% on March 28th due to COVID-19-related changes, the company implemented prioritization rules and began to throttle customers’s core functions:

“We’re implementing a few temporary restrictions designed to balance the best possible experience for all of our customers. We have placed limits on free offers to prioritize capacity for existing customers. We also have limits on certain resources for new subscriptions. These are ‘soft’ quota limits, and customers can raise support requests to increase these limits. If requests cannot be met immediately, we recommend customers use alternative regions (of our 54 live regions) that may have less demand surge. To manage surges in demand, we will expedite the creation of new capacity in the appropriate region.”

Everything from email to chat to spinning up virtual servers was impacted, with cascading effects down the chain. Turns out the “Cloud” has very real physical limits.

In the same vein, there’s been a lot of talk about upgrading from 4G to 5G cellular technology. We’re in 4G as I write this, and 4G has bandwidth limits that we’re starting to run up against. The big stories in this space in 2018 and 2019 were about the big players – Netflix, Spotify, Youtube – cutting deals with telecom companies that allowed their content to be streamed for free, while competing services were still pay-to-play. This is important because for most of the world that still pays for data, the cost of streaming a song or a movie is high. That’s both cost-as-in-price and cost-as-in-4G-bandwidth. They’re connected, you see.

Fast forward to COVID-19. People are home. Some are working, some are unfortunately not. You can’t go to the movies, you can’t go out with friends. What do you do? You FaceTime friends and family, you set up Zoom happy hours, you catch up on shows from your favorite streaming service. You video, video, video, one of the most expensive (bandwidth-wise) pieces of content that you can consume. And mostly, you can do this because you don’t pay for the bandwidth.

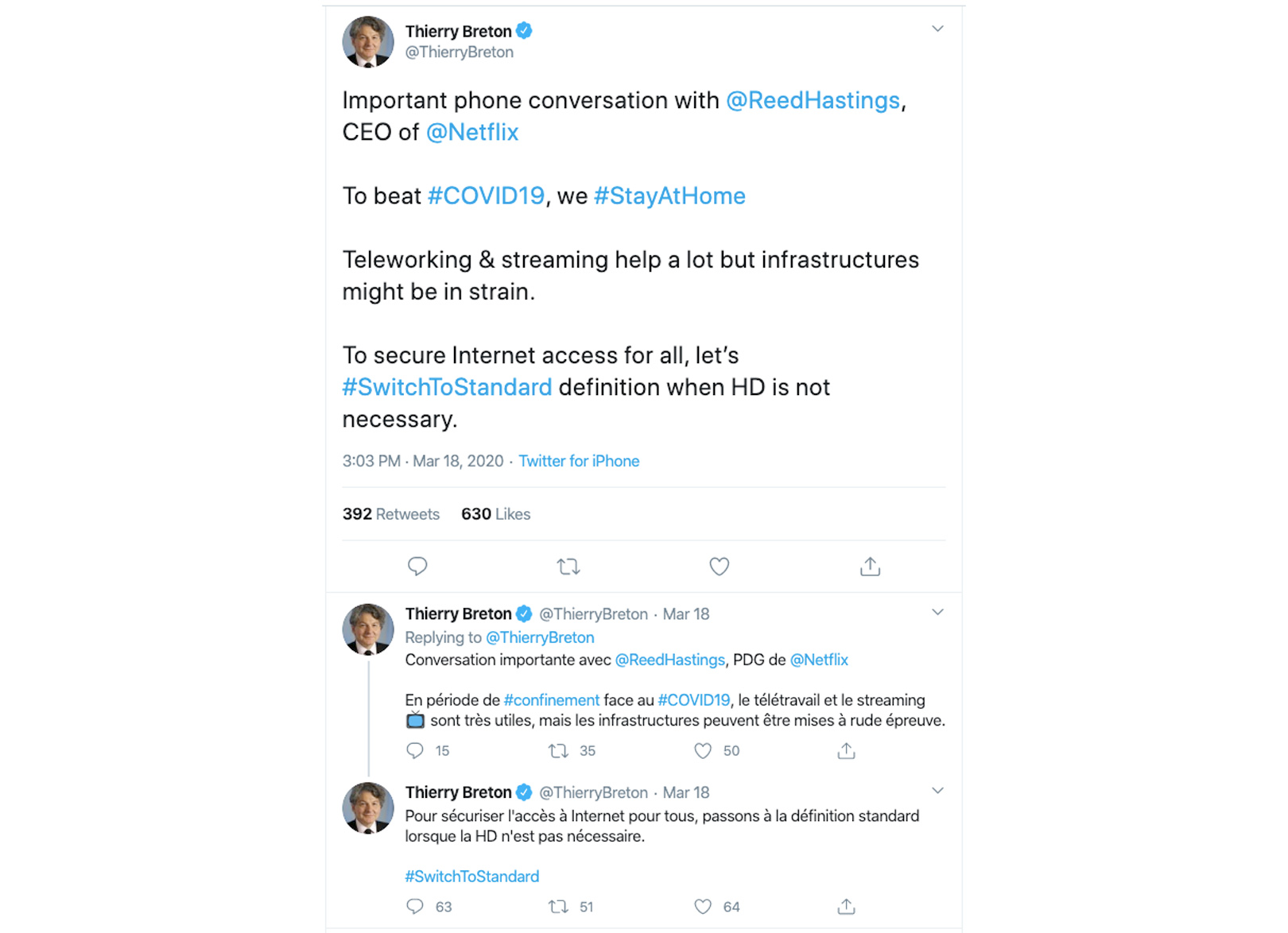

It’s an obvious strain on the internet. That’s why Netflix, Youtube, Amazon Prime Video, and Apple TV are all cutting down bitrates (quality) in their streams, to alleviate some of bandwidth stress. But it’s not just goodwill… the European Commissioner of Internal Markets is asking for it:

Which brings us back to the Google error I started my day with, a week ago. The one where the error message read in its entirety:

500. That’s an Error.

There was an error. Please try again later. That’s all we know.

Turns out, Google Cloud was having some of its own growing pains related to infrastructure: “We believe the issue with Google Cloud infrastructure components is partially resolved, and recovery is beginning. We do not have an ETA for full resolution at this point.”

If 2018 was all about the Internet of Things, and 2019 about the Internet of Privacy Violation, then I kind of expect 2020 to be about the Internet of Pipes, Capacity, and Physicality.

Well, probably not, but it sounds nice.

This was crossposted at RomanDesign.co under the title “The Internet of Pipes“