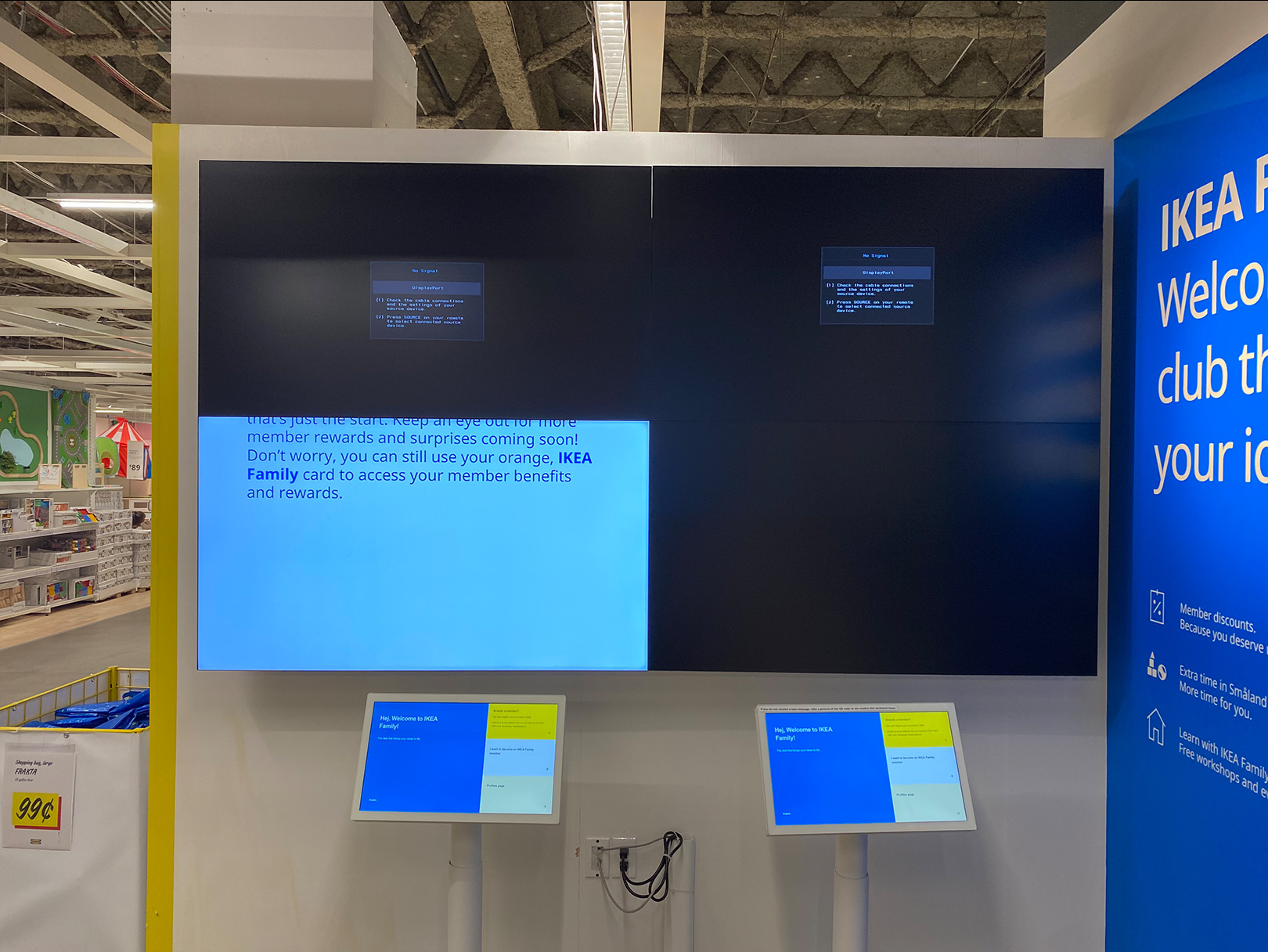

Spotted at an Ikea in Denver, Colorado. Coincidentally, there seems to be only one IKEA in Colorado. Whenever a number of different screens come together, there will be some inevitable drift towards being out-of-sync at some point. This drift can be caused by internal components (a screen burning in or out), external components (wire connections), technology (misconfigurations), or any other reason.

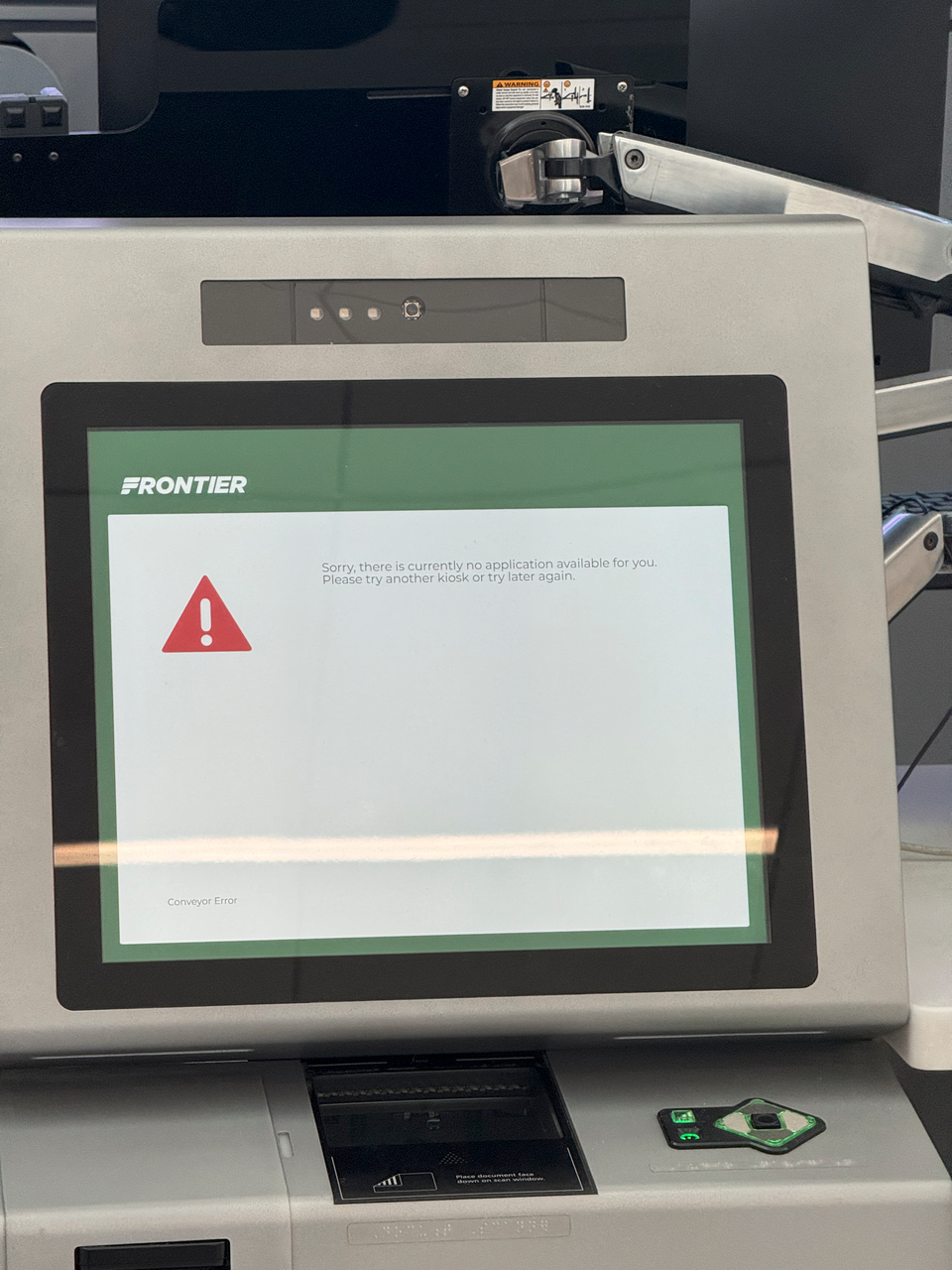

Separately, had a chance to come across this at checkout:

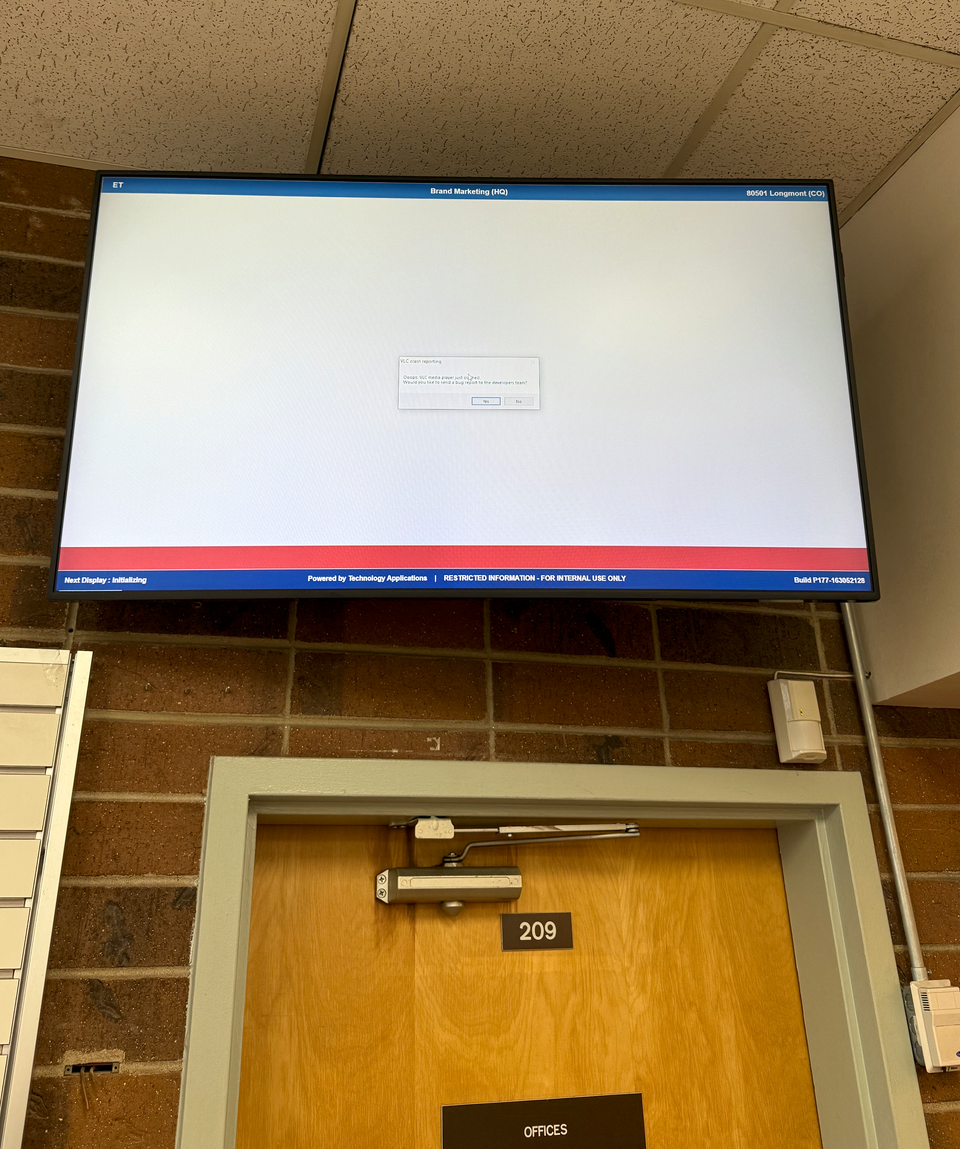

I always find it interesting to look at the OS’s that power these devices and what it looks like when they no longer work properly.

Your error screen has to account for three types of end-users: the general audience (people looking at the screen and interacting with it as consumers), the local administrators (likely non-technical local staff), and remote ‘master’ administrators.

For the general users, you want to lock down the device so that they’re not able to manipulate either the hardware or software to do anything except for what you’ve allowed them to do. Sometimes this means using off the shelf hardware like an iPad but with special casing to close off all ports and buttons, sometimes there is a custom hardware design. Buying a microcomputer and a screen and fabbing a custom case isn’t all that expensive, but there are also enough special-purposes devices being created for checkouts, ordering, and overall in-store experiences that it makes much more sense to buy rather than build.

Then the local administration – Sometimes this is a physical key to unlock a device or a secret combination of button presses software-side. But when it crashes, how do you enable the local admin repair it? Because, you don’t want to give up the keys to the house if the consumer-facing UI errors out, but you also want to be flexible enough to be able to fix things when they go wrong. It’s the little details to pay attention to. The few buttons on the top, perhaps? Or a plug point to run remote diagnostics hardware-side.

Then the remote master administration: these folks configure the devices via remote device management (RDM) tools, often hundreds to thousands at a time, and deploy them, do over the air fixes, and so on. Sometimes, you do need to call HQ for troubleshooting. But the worst is when you’ve locked down the device so far that you need to completely wipe it because it no longer has an internet connection to be remotely fixed, and isn’t open enough to be fixed locally. You’re 95% of the way to bricking it at the point.

When I was working with these sorts of projects in at a jewelry company, that was the first. We set up a few devices as a test run, and I ended up going back and forth between HQ and the in-store locations as minute changes cascaded incorrectly, or an IP address would change, or someone would change a local network password and suddenly I lost access to a device. Remote device management is a fun space, but with lots of hidden complexity.